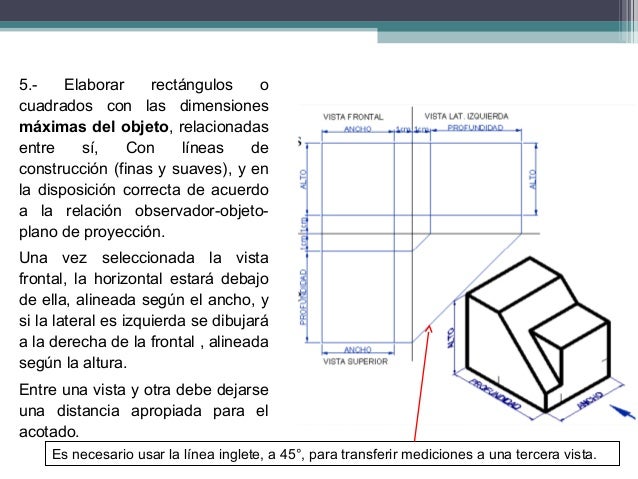

Vista Frontal Lateral Superior Inferior

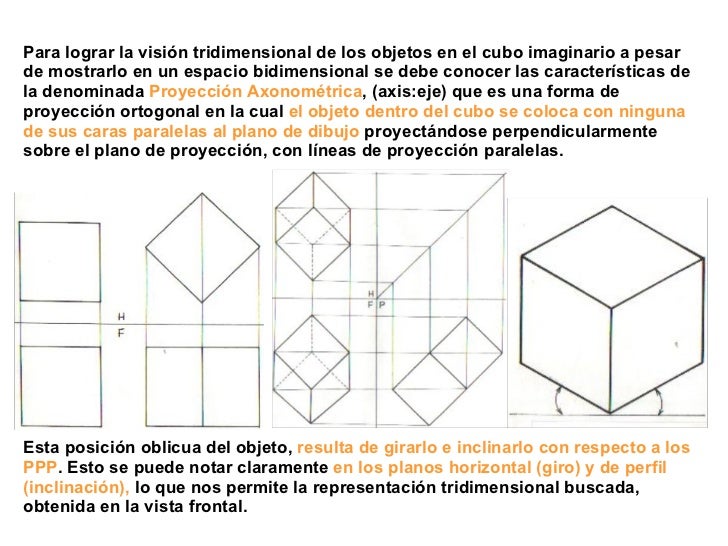

Download Read Online perspectiva cavaleira perspectiva isometrica TECNICO- Esta Norma fixa a forma de representacao aplicada em desenho tecnico. Como:. Metodo de projecao ortografica. Denominacao das vistas: de acordo com a figura abaixo sao os seguintes: - vista frontal (a).

vista superior (b). vista lateral esquerda (c). vista lateral direita (d). vista inferior (e). 2016 Desenho Tecnico. Trata-se da planificacao de pecas, desenhos contendo as formas detalhadas e suas respectivas dimensoes, de utensilios em geral,. Denominaremos Vista Frontal, vermelha para a Vista Lateral e Azul para Vista.

O passo seguinte sera o rebatimento do plano auxiliar (?' '), CAPITULO 1: ELEMENTOS BASICOS DO DESENHO TECNICO. A figura ilustra um cubo Figura superior esquerda: prisma de base hexagonal e dois cilindros (parte externa e o furo). Figura superior b) No sistema do 3? Diedro a vista lateral esquerda fica a esquerda da frontal e a vista lateral direita fica a direita da Desenho Tecnico 26.

Nao e necessario utilizar seis vistas para representar objetos relativamente simples, geralmente utilizam-se apenas tres vistas (superior, frontal e lateral). Esta combinacao pode variar e no trabalho pratico a escolha da combinacao das vistas e fundamental para descrever da forma mais clara e desenho tecnico.

Observe, na figura A, que a parte obliqua apareceu representada defor- mada nos planos de projecao horizontal e lateral. Vistas auxiliares. A Neste exemplo, a face obliqua apareceu deformada nas vistas superior e lateral esquerda. Dessa forma, o furo passante e a parte arredondada aparecem. Ou ate 6 vistas. Mesmo com o uso de somente tres vistas (frontal, superior e lateral) pode haver uma confusao de linhas ocultas, que dificultara a leitura do desenho.

4.4.3 Vistas auxiliares. Usado para ilustrar faces fora dos planos ortogonais, no caso de faces inclinadas, as vistas auxiliares serao vistas no proximo capitulo Em Desenho Tecnico, denomina-se vista ortografica a figura resultante da projecao cilindrica ortogonal do obje- to sobre um plano de referencia. V ista Anterior. V.F = V ista Frontal. S = V ista Superior.

Hi, I'm trying to translate these expressions from Spanish to English. They're all related to views of 3D objects. Here's my try: - Vista frontal.

= V ista Lateral Esquerda. Desenho Tecnico Mecanico I. Projecao Cilindrica. Projecao Ortogonal. PROJECOES e reforcar contornos. 04 - tracar a lateral esquerda. 03 - tracar a face superior Tecnico Mecanico I.

Projecao ortogonal - 1? Diedro - Vista frontal APOSTILA DE DESENHO TECNICO. Figura 4.6 – Projecao de um objeto no 3?

Com relacao a vista principal, a vista frontal, as demais vistas sao organizadas da seguinte maneira: a vista superior fica acima, a vista inferior fica abaixo, a vista lateral esquerda fica a esquerda,.

. Standard anatomical terms of location deal unambiguously with the of, including humans. All (including humans) have the same basic – they are strictly in early embryonic stages and largely bilaterally symmetrical in adulthood. That is, they have mirror-image left and right halves if divided down the centre.

For these reasons, the basic directional terms can be considered to be those used in vertebrates. By extension, the same terms are used for many other organisms as well. While these terms are standardized within specific fields of, there are unavoidable, sometimes dramatic, differences between some disciplines. For example, differences in terminology remain a problem that, to some extent, still separates the from that used in the study of various other zoological categories.

Because of differences in the way humans and other animals are structured, different terms are used according to the and whether an animal is a. Standardized and terms of location have been developed, usually based on and words, to enable all biological and medical scientists to precisely delineate and communicate information about animal bodies and their component organs, even though the meaning of some of the terms often is context-sensitive. The and share a substantial heritage and common structure, so many of the same terms are used to describe location. To avoid ambiguities this terminology is based on the anatomy of each animal in a standard way. For humans, one type of vertebrate, anatomical terms may differ from other forms of vertebrates.

For one reason, this is because humans have a different and, unlike animals that rest on four limbs, humans are considered when describing anatomy as being in the. Thus what is on 'top' of a human is the, whereas the 'top' of a dog may be its back, and the 'top' of a could refer to either its left or its right side. For, standard application of locational terminology often becomes difficult or debatable at best when the differences in are so radical that common concepts are not and do not refer to common concepts. For example, many species are not even.

In these species, terminology depends on their type of symmetry (if any). Standard anatomical position. Main article: Because can change orientation with respect to their environment, and because like and can change position with respect to the main body, positional descriptive terms need to refer to the animal as in its. All descriptions are with respect to the organism in its standard anatomical position, even when the organism in question has appendages in another position.

This helps avoid confusion in terminology when referring to the same organism in different postures. In humans, this refers to the body in a standing position with arms at the side and palms facing forward (thumbs out). While the universal vertebrate terminology used in veterinary medicine would work in human medicine, the human terms are thought to be. Combined terms.

Dorsolateral flattening in the anatomy of a gives its body a triangular cross-section Many anatomical terms can be combined, either to indicate a position in two axes simultaneously or to indicate the direction of a movement relative to the body. For example, 'anterolateral' indicates a position that is both anterior and lateral to the body axis (such as the bulk of the muscle). In, an image may be said to be 'anteroposterior', indicating that the beam of X-rays pass from their source to patient's body wall through the body to exit through body wall. There is no definite limit to the contexts in which terms may be modified to qualify each other in such combinations. Generally the modifier term is truncated and an 'o' or an 'i' is added in prefixing it to the qualified term. For example, a view of an animal from an aspect at once dorsal and lateral might be called a 'dorsolateral' view; and the effect of dorsolateral flattening in an organism such as a gives its body a triangular cross section.

Again, in describing the of an organ or of an animal such as many of the, one might speak of it as 'dorsiventrally' flattened as opposed to bilaterally flattened animals such as. Where desirable three or more terms may be or, as in 'anteriodorsolateral'. Such terms sometimes used to be hyphenated, but the modern tendency is to omit the hyphen. There is however little basis for any strict rule to interfere with choice of convenience in such usage. Anatomical planes in a human Three basic reference planes are used to describe location. The is a plane parallel to the.

All other sagittal planes (referred to as parasagittal planes) are parallel to it. It is also known as a 'longitudinal plane'. The plane is a Y-Z plane, perpendicular to the ground. The median plane or midsagittal plane is in the midline of the body, and divides the body into left and right (sinister and dexter) portions. This passes through the, and, in animals, the. The median plane can also refer to the midsagittal plane of other structures, such as a digit. The or coronal plane divides the body into dorsal and ventral (back and front, or posterior and anterior) portions.

For post- humans a is vertical and a transverse plane is horizontal, but for embryos and quadrupeds a coronal plane is horizontal and a transverse plane is vertical. A longitudinal plane is any plane perpendicular to the transverse plane. The and the are examples of longitudinal planes. A, also known as a cross-section, divides the body into cranial and caudal (head and tail) portions. In human anatomy.

A transverse (also known as horizontal) plane is an X-Z plane, parallel to the ground, which (in humans) separates the from the or, put another way, the head from the feet. A coronal (also known as frontal) plane is a X-Y plane, to the ground, which (in humans) separates the anterior from the posterior, the front from the back, the ventral from the dorsal.

Or near-spheroid organs such as may be measured by 'long' and 'short' axis. ^ Fairly common use. ^ Uncommon use. Equivalent to one-half of the left-right axis. To begin with, distinct, polar-opposite ends of the are chosen.

By definition, each pair of opposite points defines an. In a bilaterally symmetrical organism, there are 6 polar opposite points, giving three axes that intersect at right angles – the x, y, and z axes familiar from three-dimensional geometry. The terms 'intermediate', 'ipsilateral', 'contralateral', 'superficial', and 'deep', while indicating directions, are relative terms and thus do not properly define fixed anatomical axes. Also, while the 'rostrocaudal' and anteroposterior directionality are equivalent in a significant portion of the human body, they are different directions in other parts of the body. Main terminologies Superior and inferior In anatomical terminology superior (from, meaning 'above') is used to refer to what is above something, and inferior (from, meaning 'below') to what is below it. For example, in the the most superior part of the human body is the head, and the most inferior is the feet. As a second example, in humans the is superior to the but inferior to the.

Anterior and posterior. 'anterior' redirects here. For posterior, see. Anterior refers to what is in front (from ante, meaning 'before') and posterior, what is to the back of the subject (from post, meaning 'after'). For example, in a dog the is anterior to the eyes and the is considered the most posterior part; in many the openings are posterior to the eyes, but anterior to the tail.

Medial and lateral Lateral (from lateralis, meaning 'to the side') refers to the sides of an animal, as in 'left lateral' and 'right lateral'. The term medial (from medius, meaning 'middle') is used to refer to structures close to the centre of an organism, called the 'median plane'. For example, in a human, imagine a line down the center of the body from the head though the navel and going between the legs— the medial side of the foot would be the big toe side; the medial side of the knee would be the side adjacent to the other knee. To describe the sides of the knees touching each other would be 'right medial' and 'left medial'. The terms 'left' and 'right' are sometimes used, or their Latin alternatives (: dexter; 'right',: sinister; 'left').

However, as left and right sides are, using these words is somewhat confusing, as structures are duplicated on both sides. For example, it is very confusing to say the of a is 'right of' the left, but is 'left of' the right, but much easier and clearer to say 'the dorsal fin is medial to the pectoral fins'. Derived terms include:. Contralateral (from contra, meaning 'against'): on the side opposite to another structure. For example, the right arm and leg are represented by the left, i.e.,. Ipsilateral (from ipse, meaning 'same'): on the same side as another structure.

For example, the left arm is ipsilateral to the left leg. Bilateral (from bis, meaning 'twice'): on both sides of the body. For example, bilateral (removal of testes on both sides of the body's axis) is surgical. Unilateral (from unus, meaning 'one'): on one side of the body.

For example, unilateral is. And correspond to medial and lateral, respectively, regarding the distal segment's vector relative to the proximal segment's vector.

Proximal and distal. Anatomical directional reference The terms proximal (from proximus, meaning 'nearest') and distal (from distare, meaning 'to stand away from') are used to describe parts of a feature that are close to or distant from the main mass of the body, respectively. Thus the upper arm in humans is proximal and the hand is distal. These terms are particularly useful when describing such as, or indeed any structure that extends that can potentially move separately from the main body.

Although the direction indicated by 'proximal' and 'distal' is always respectively towards or away from the point of attachment, a given structure can be either proximal or distal in relation to another point of reference. Thus the elbow is distal to a wound on the upper arm, but proximal to a wound on the lower arm. This terminology is also employed in molecular biology and therefore by extension is also used in chemistry. Specifically as referring to the atomic loci of molecules from the overall moiety of a given compound. Central and peripheral Central and peripheral are terms that are closely related to concepts such as proximal and distal, but they are so widely applicable that in many respects their flexibility makes them hard to define.

Loosely speaking, they distinguish near and far, inside and out, or even organs of vital importance such as heart and lungs, from peripheral organs such as fingers, that undoubtedly may be important, but which it may not be life-threatening to dispense with. Examples of the application of the terms are the distinction between and, and between peripheral blood vessels and the central circulatory organs, such as the heart and major vessels. The terms also can apply to large and complex molecules such as proteins, where central amino acid are protected from antibodies or the like, but peripheral residues are important in docking and other interactions. Other examples include Central and peripheral circadian clocks, and central versus peripheral vision. Superficial and deep These two terms relate to the distance of a structure from the surface of an animal. Deep (from ) refers to something further away from the surface of the organism. For example, the of the abdomen is deep to the skin.

'Deep' is one of the few anatomical terms of location derived from rather than Latin – the anglicised Latin term would have been 'profound' (from profundus, meaning 'due to depth'). Superficial (from superficies, meaning 'surface') refers to something near the outer surface of the organism. For example, in the is superficial to the. Dorsal and ventral These two terms, used in anatomy and, refer to back ( dorsal) and front or belly ( ventral) of an organism. The dorsal (from dorsum, meaning 'back') surface of an organism refers to the back, or upper side, of an organism.

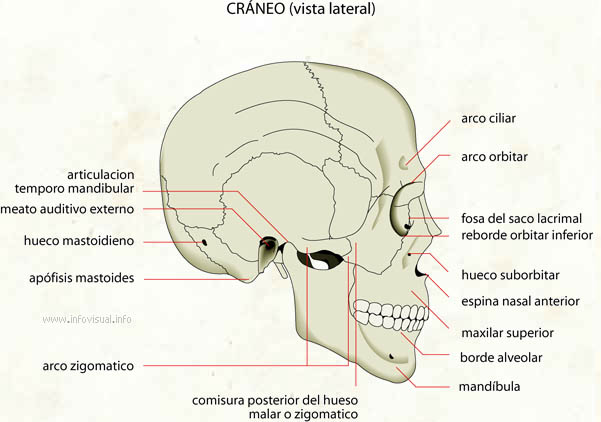

If talking about the skull, the dorsal side is the top. The ventral (from venter, meaning 'belly') surface refers to the front, or lower side, of an organism. For example, in a fish the are dorsal to the, but ventral to the. Cranial and caudal. In the human skull the terms rostral and caudal are adapted to the curved of Specific terms exist to describe how close or far something is to the head or tail of an animal. To describe how close to the head of an animal something is, three distinct terms are used:. Rostral (from rostrum, meaning 'beak, nose'), meaning situated toward the oral or nasal region, or in the case of the brain, toward the tip of the frontal lobe.

Cranial (from κρανίον, meaning 'skull') or cephalic (from κεφαλή, meaning 'head'). Caudal (from cauda, meaning 'tail') is used to describe how close something is to the end of an organism, For example, in the, the eyes are caudal to the nose and rostral to the back of the head. These terms are generally preferred in veterinary medicine and not used as often in human medicine. In humans, 'cranial' and 'cephalic' are used to refer to the skull, with 'cranial' being used more commonly.

The term 'rostral' is rarely used in human anatomy, apart from embryology, and refers more to the front of the face than the superior aspect of the organism. Similarly, the term 'caudal' is only occasionally used in human anatomy. This is because the brain is situated at the superior part of the head whereas the nose is situated in the anterior part. Thus the 'rostrocaudal axis' refers to a C shape (see image). Other terms and special cases Anatomical landmarks The location of anatomical structures can also be described with relation to different. Structures may be described as being at the level of a specific, depending on the section of the the structure is. The position is often abbreviated.

For example, structures at the level of the fourth cervical vertebra may be abbreviated as 'C4', at the level of a thoracic vertebra 'T4', at the level of a lumbar vertebra 'L3'. Because the and coccyx are fused, they are not often used to provide location. References may also take origin from, made to landmarks that are on the skin or visible underneath.

For example, structures may be described relative to the, the or the., theoretical lines drawn through structures, are also used to describe anatomical location. For example, the mid-clavicular line is used as part of the in medicine to feel the of the. Mouth and teeth. Main article: Fields such as, and dentistry apply special terms of location to describe the mouth and teeth. This is because although teeth may be aligned with their main axes within the jaw, some different relationships require special terminology as well; for example teeth also can be rotated, and in such contexts terms like 'anterior' or 'lateral' become ambiguous. Terms such as 'distal' and 'proximal' are also redefined to mean the distance away or close to the. Terms used to describe structures include 'buccal' (from bucca, meaning 'cheek') and 'palatal' (from ) referring to structures close to the and respectively.

Hands and feet. Anatomical terms used to describe a human hand Several anatomical terms are particular to the hands and feet For improved clarity, the directional term palmar (from palma, meaning 'palm of the hand') is usually used to describe the front of the hand, and dorsal is the back of the hand. For example, the top of a 's is its dorsal surface; the underside, either the palmar (on the forelimb) or the plantar (on the hindlimb) surface. The is palmar to the of muscles which flex the fingers, and the is so named because it is on the dorsal side of the foot. Volar can also be used to refer to the underside of the or, which are themselves also sometimes used to describe location as and.

For example, volar pads are those on the underside of hands, fingers, feet, and toes. These terms are used to avoid confusion when describing the median surface of the hand and what is the 'anterior' or 'posterior' surface – 'anterior' can be used to describe the of the hand, and 'posterior' can be used to describe the back of the hand and arm. This confusion can arise because the forearm can and. Similarly, in the forearm, for clarity, the sides are named after the bones. Structures closer to the are radial, structures closer to the are ulnar, and structures relating to both bones are referred to as radioulnar. Similarly, in the lower leg, structures near the (shinbone) are tibial and structures near the are fibular (or peroneal).

Rotational direction Most terms of anatomical location are relative to linear motion along the X- Y- and Z-axes, but there are other as well, in particular, rotation around any of those three axes. Anteversion and retroversion are complementary anatomical terms of location, describing the degree to which an anatomical structure is rotated forwards (towards the front of the body) or backwards (towards the back of the body) respectively, relative to some datum position.

The terms also describe the positioning of surgical implants, such as in. Anteversion refers to an anatomical structure being tilted further forward than normal, whether pathologically or incidentally. For example, there may be a need to measure the anteversion of the neck of a bone such as a femur. For example, a woman's typically is anteverted, tilted slightly forward. A misaligned may be anteverted, that is to say tilted forward to some relevant degree.

Retroversion is rotation around the same axis as that of anteversion, but in the opposite sense, that is to say, tilting back. A structure so affected is described as being. As with anteversion, retroversion is a completely general term and can apply to a backward tilting of such hard structures as bones, soft organs such as uteri, or surgical implants. Other directional terms Several other terms are also used to describe location. These terms are not used to form the fixed axes. Terms include:. Axial (from axis, meaning 'axle'): around the central axis of the organism or the extremity.

Two related terms, 'abaxial' and 'adaxial', refer to locations away from and toward the central axis of an organism, respectively. Parietal (from paries, meaning 'wall'): pertaining to the wall of a body cavity. For example, the is the lining on the inside of the abdominal cavity. Parietal can also refer specifically to the of the skull or associated structures. Posteromedial (from posterus, meaning 'coming after', and medius, meaning 'middle'): situated towards the middle of the posterior surface.

Terminal (from terminus, meaning 'boundary or end') at the extremity of a (usually projecting) structure, as in '.an antenna with a terminal sensory hair'. Visceral and viscus (from viscera, meaning 'internal organs'): associated with organs within the body's cavities. For example, the is covered with a lining called the visceral as opposed to the parietal pertoneum. Viscus can also be used to mean 'organ'.

For example, the stomach is a viscus within the abdominal cavity. Prefixes, suffixes, and other modifiers Directional and locational prefixes can modify many anatomical and morphological terms, sometimes in formally standard usage, but often attached arbitrarily according to need or convenience. Prefixes. Sub- (from sub, meaning 'preposition beneath, close to, nearly etc') appended as a prefix, with or without the hyphen, qualifies terms in various senses. Consider subcutaneous as meaning beneath the skin, subterminal meaning near to the end of a structure. Sub- also may mean 'nearly' or 'more-or-less'; for instance subglobular means almost globular.

In many usages sub- is similar in application to 'hypo-'. Hypo- (from ὑπό, meaning 'under') Like 'sub' in various senses as in hypolingual nerve beneath the tongue, or hypodermal fat beneath the skin. Infra- (from infra, meaning 'preposition beneath, below etc') Similar to 'sub'; a direct opposite to super- and supra-, as in.

Inter- (from inter, meaning 'between'): between two other structures. For example, the is intermediate to the left arm and the contralateral (right) leg. The run between the ribs.

Inferior Lateral Heart

Super- or Supra- (from super, supra, meaning 'above, on top of, beyond etc') appended as a prefix, with or without the hyphen, as in or Suffixes.ad (from ad', meaning 'towards or up to') Commonly when, for example, one anatomical feature is nearer to something than another, one may use an expression such as 'nearer the distal end' or 'distal to'. However, an unambiguous and concise convention is to use the Latin suffix -ad, meaning 'towards', or sometimes 'to'.

So for example, ' distad' means 'in the distal direction', and 'distad of the femur' means 'beyond the femur in the distal direction'. The suffix may be used very widely, as in the following examples: anteriad (towards the anterior), apicad (towards the apex), basad (towards the basal end), caudad, centrad, cephalad (towards the cephalic end), craniad, dextrad, dextrocaudad, dextrocephalad, distad, dorsad, ectad (towards the ectal, or exterior, direction), entad (towards the interior), laterad, mediad, mesad, neurad, orad, posteriad, proximad, rostrad, sinistrad, sinistrocaudad, sinistrocephalad, ventrad.

Specific animals and other organisms The large variety of present in invertebrates presents a difficult problem when attempting to apply standard directional terms. Depending on the organism, some terms are taken by analogy from vertebrate anatomy, and appropriate novel terms are applied as needed. Some such borrowed terms are widely applicable in most invertebrates; for example proximal, literally meaning 'near' refers to the part of an appendage nearest to where it joins the body, and distal, literally meaning 'standing away from' is used for the part furthest from the point of attachment. In all cases, the usage of terms is dependent on the of the organism. For example, especially in organisms without distinct heads for reasons of broader applicability, 'anterior' is usually preferred.

Humans As humans are approximately organisms, anatomical descriptions usually use the same terms as those for vertebrates and other members of the taxonomic group. However, for historical and other reasons, standard human directional terminology has several differences from that used for other bilaterally symmetrical organisms.

The terms of zootomy and anatomy came into use at a time when all scientific communication took place in Latin. In their original Latin forms the respective meanings of 'anterior' and 'posterior' are in front of (or before) and behind (or after), those of 'dorsal' and 'ventral' are toward the spine and toward the belly, and those of 'superior' and 'inferior' are above and below. Humans, however, have the rare property of having an upright torso. This makes their anterior/posterior and dorsal/ventral directions the same, and the inferior/superior directions necessary. Most animals, furthermore, are capable of moving relative to their environment.

So while 'up' might refer to the direction of a standing human's head, the same term ('up') might be used to refer to the direction of the belly of a human. It is also necessary to employ some specific anatomical knowledge in order to apply the terminology unambiguously: For example, while the ears would be superior to (above) the shoulders in a human, this fails when describing the, where the shoulders are above the ears. Thus, in terminology, the ears would be cranial to (i.e., 'toward the head from') the shoulders in the armadillo, the, the, or any other vertebrate, including the human. Likewise, while the belly is considered anterior to (in front of) the back in humans, this terminology fails for the flounder, the armadillo, and the dog. In veterinary terms, the belly would be ventral ('toward the abdomen') in all vertebrates.

While it would be possible to introduce a system of axes that is completely consistent between humans and other vertebrates by having two separate pairs of axes, one used exclusively for the head (e.g., anterior/posterior and inferior/superior) and the other exclusively for the torso (e.g., dorsal/ventral and caudal/rostral, or 'toward the tail'/'toward the beak'), doing so would require the renaming of many anatomical structures. Asymmetrical and spherical organisms. Figure 5: Asymmetrical and spherical.

(a) An organism with an asymmetrical, amoeboid, body plan ( Amoeba proteus – an amoeba). (b) An organism with a spherical body plan ( Actinophrys sol – a ). In organisms with a changeable shape, such as organisms, most directional terms are meaningless, since the shape of the organism is not constant and no distinct axes are fixed. Similarly, in organisms, there is nothing to distinguish one line through the centre of the organism from any other.

An indefinite number of triads of mutually perpendicular axes could be defined, but any such choice of axes would be useless, as nothing would distinguish a chosen triad from any others. In such organisms, only terms such as superficial and deep, or sometimes proximal and distal, are usefully descriptive. Figure 6: Four individuals of Phaeodactylum tricornutum, a with a fixed elongated shape. Elongated organisms In organisms that maintain a constant shape and have one dimension longer than the other, at least two directional terms can be used. The long or longitudinal axis is defined by points at the opposite ends of the organism. Similarly, a perpendicular transverse axis can be defined by points on opposite sides of the organism. There is typically no basis for the definition of a third axis.

Usually such organisms are (free-swimming), and are nearly always viewed on, where they appear essentially two-dimensional. In some cases a third axis can be defined, particularly where a non-terminal or other unique structure is present. Figure 7: Organisms where the ends of the long axis are distinct. ( Paramecium caudatum, above, and, below.) Some elongated have distinctive ends of the body. In such organisms, the end with a mouth (or equivalent structure, such as the in or ), or the end that usually points in the direction of the organism's (such as the end with the in ), is normally designated as the anterior end. The opposite end then becomes the posterior end. Properly, this terminology would apply only to an organism that is always (not normally attached to a surface), although the term can also be applied to one that is (normally attached to a surface).

Figure 8: A cluster of, showing the apical-basal axes. Organisms that are attached to a, such as, or some also have distinctive ends. The part of the organism attached to the substrate is usually referred to as the basal end (: basis, 'support/foundation'), whereas the end furthest from the attachment is referred to as the apical end (: apex, 'peak/tip'). Radially symmetrical organisms include those in the group – primarily and the. Adult, such as, and others are also included, since they are pentaradial, meaning they have five. Echinoderm are not included, since they are. Radially symmetrical organisms always have one distinctive axis.

(jellyfish, sea anemones and corals) have an incomplete digestive system, meaning that one end of the organism has a mouth, and the opposite end has no opening from the gut (coelenteron). For this reason, the end of the organism with the mouth is referred to as the oral end (: os, 'mouth'), and the opposite surface is the aboral end (: ab-, prefix meaning 'away from'). Unlike vertebrates, cnidarians have no other distinctive axes. 'Lateral', 'dorsal', and 'ventral' have no meaning in such organisms, and all can be replaced by the generic term peripheral (: περί, 'around'). Medial can be used, but in the case of radiates indicates the central point, rather than a central axis as in vertebrates.

Thus, there are multiple possible radial axes and medio-peripheral (half-) axes. However, it is noteworthy that some biradially symmetrical do have distinct 'tentacular' and 'pharyngeal' axes and are thus anatomically equivalent to animals.

As with vertebrates, that move independently of the body ( in and ), have a definite proximodistal axis (Fig. See also: and Two specialized terms are useful in describing views of legs and.

Inferior Lateral Leads

Prolateral refers to the surface of a leg that is closest to the anterior end of an arachnid's body. Retrolateral refers to the surface of a leg that is closest to the posterior end of an arachnid's body. Because of the unusual nature and positions of the eyes of the (spiders), and their importance in taxonomy, evolution and anatomy, special terminology with associated abbreviations has become established in arachnology. Araneae normally have eight eyes in four pairs. All the eyes are on the of the, and their sizes, shapes and locations are characteristic of various spider families and other. In some taxa not all four pairs of eyes are present, the relevant species having only three, two, or one pair of eyes. Some species (mainly ) have no functional eyes at all.

In what is seen as the likeliest ancestral arrangement of the eyes of the Araneae, there are two roughly parallel, horizontal, symmetrical, transverse rows of eyes, each containing two symmetrically placed pairs, respectively called: anterior and posterior lateral eyes (ALE) and (PLE); and anterior and posterior median eyes (AME) and (PME). As a rule it is not difficult to guess which eyes are which in a living or preserved specimen, but sometimes it can be. Apart from the fact that in some species one or more pairs may be missing, sometimes eyes from the posterior and anterior rows may be very close to each other, or even fused. Also, either one row or both might be so grossly curved that some of the notionally anterior eyes actually may lie posterior to some of the eyes in the posterior row. In some species the curve is so gross that the eyes apparently are arranged into two anteroposterior parallel rows of eyes.